Model Registry Overview

This page explains how the GitLab Model Registry fits into a typical machine learning workflow and how to use it as a curation layer on top of experiments.

A complete end-to-end example (dataset → training → promotion → inference) is available here:

End-to-end tutorial: Model Registry Demo

The tutorial walks through a working example that uses MLflow to automate much of this process. This page focuses on the concepts and lifecycle so you understand what is happening and why.

Mental model

The most important idea is that experiments and registry versions serve different purposes.

Machine learning workflows naturally produce a lot of intermediate results. You try different parameters, adjust data, change architectures, and rerun training many times. Most of these runs are exploratory. Only a small fraction of them should ever be treated as official, reusable models.

The system is designed around that distinction.

Experiments and runs = iteration

Experiments are your working area. They are where you explore, test hypotheses, and iterate quickly. Every training run becomes a detailed record of what happened during that attempt.

A single run captures the full context of a training event: the parameters used, the metrics produced, the dataset lineage, and the artifacts generated by the job. If a run succeeds, fails, or behaves unexpectedly, you still keep the trace. That historical record is valuable for debugging, comparison, and reproducibility.

It is normal for an experiment to contain dozens or hundreds of runs. The goal here is not polish — it is visibility and learning. Runs are intentionally high-churn and optimized for iteration speed.

Model Registry = curation

The Model Registry sits one level above experimentation. It is not about exploration; it is about publication.

A registry entry represents a stable model identity. Versions inside the registry represent curated releases of that model. Each version is created deliberately, with provenance attached, and intended for consumption by other systems or teams.

This is where governance begins to matter. Registry versions are long-lived. They may be deployed into production, referenced in reports, or embedded in pipelines. Unlike training runs, registry entries should feel intentional and stable.

The key principle is simple: not every run becomes a registry version. Promotion is a conscious act of curation.

Lifecycle overview

A typical workflow looks like this:

Dataset → Training Runs → Promotion → Model Registry → Consumers

This flow separates experimentation from publication while keeping them tightly linked through provenance.

1. Dataset curation

The lifecycle starts with a dataset snapshot. Instead of treating data as an implicit input, the workflow logs the dataset itself as an experiment run.

This dataset run records identity information such as manifest hashes, sample counts, timestamps, and optional frozen artifacts. The result is a dataset run ID that can be referenced later by training jobs.

This step makes training auditable. You can prove exactly which dataset was used, reconstruct it later, and compare results across versions. Treating datasets as first-class experiment artifacts prevents silent drift and improves reproducibility.

2. Training

Training runs consume a dataset run and produce candidate models.

Each training job logs the dataset lineage alongside hyperparameters, metrics, and model artifacts. The result is a fully traceable record connecting model behavior back to the data that produced it.

At this stage, models are still candidates. They live inside the experiment tracking system and are meant for evaluation and comparison. You may run many jobs in parallel, sweep parameters, or repeat experiments over time. Only a subset of these runs should ever be promoted.

The purpose of training is exploration. The purpose of promotion is selection.

3. Promotion (curation gate)

Promotion is the boundary between experimentation and publication.

During promotion, a training run is evaluated against policy. This policy might include metric thresholds, manual approval flags, validation checks, or governance requirements. If a run qualifies, it is converted into a registry version.

The registry version does not replace the original run. Instead, it becomes a curated reference to it. Provenance metadata links the version back to the exact training run and artifact path. This preserves the full lineage while presenting a clean, stable interface to consumers.

This separation is intentional. Experimentation remains fast and flexible, while publishing remains controlled and auditable.

4. Consumption

Consumers should interact with the registry, not raw run IDs.

Downstream systems typically want stable references such as “latest approved,” a semantic version number, or an environment-specific release. Registry versions provide that contract.

Because each version stores enough provenance to resolve the original artifact, consumers can fetch the correct model, verify integrity, and reproduce behavior without needing to understand the experiment history. Deployment pipelines remain stable even while experimentation continues upstream.

Visual walkthrough (UI examples)

This section is designed to embed screenshots from the end-to-end demo. The goal is to connect the concepts above to what users actually see in the GitLab interface.

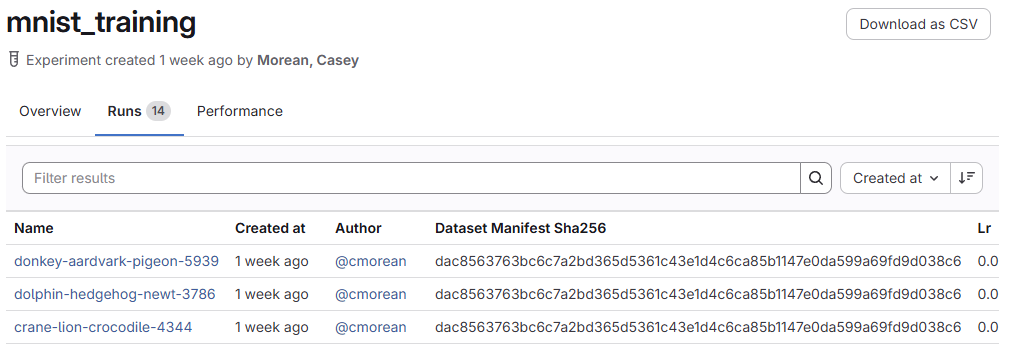

Experiment tracking view

Analyze → Model Experiments

This view shows an experiment containing multiple runs. Each row represents a training attempt. Users can compare metrics, inspect parameters, and drill into artifacts. This is the exploration layer: dense, information-rich, and intentionally noisy.

Run detail view

Analyze → Model Experiments → Experiment Name

A run page exposes the full provenance of a training job: dataset lineage, hyperparameters, logged artifacts, and metrics. This is the raw source of truth that promotion draws from.

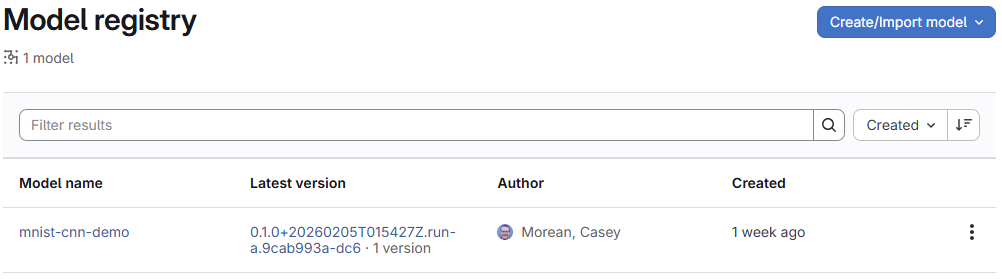

Model Registry view

Deploy → Model Regiustry

The registry presents a curated surface. Instead of hundreds of runs, you see a small number of intentional versions. Each version links back to its source run while providing a stable identity for consumers.

Why not publish every run?

Publishing every run would collapse the distinction between experimentation and curation.

Experiments are noisy by design. They contain failed attempts, partial jobs, exploratory configurations, and unstable results. That noise is useful for learning but harmful for downstream consumers.

The registry is intentionally quieter. It represents decisions rather than attempts.

A useful analogy is to think of experiment runs as a lab notebook and the registry as a published paper. The notebook contains everything. The paper contains what you stand behind.

Artifact strategy

The tutorial demonstrates a lightweight registry pattern where training runs remain the authoritative storage location for artifacts, and registry versions store provenance plus pointers.

This approach avoids duplicating large files, keeps promotions fast, and maintains a clean lineage chain. The registry acts as a curated index rather than a second artifact warehouse.

Organizations can extend this pattern if needed. Some teams choose to copy artifacts into long-term registry storage, apply retention policies, or require signing and integrity checks. The architecture supports these governance layers without changing the core workflow.

Versioning approach

Registry versions follow semantic versioning principles so humans can reason about releases.

A version number communicates intent: stability, compatibility, and progression. Build metadata and provenance fields provide machine-readable traceability back to the exact training run.

Promotion scripts can enforce version policies, automate patch increments, or implement staged release channels such as development, staging, and production. The important point is that version numbers describe meaning for people, while metadata preserves exact identity for systems.

Both layers are necessary.

When to use the Model Registry

The Model Registry is appropriate whenever a model crosses a boundary: between teams, environments, or lifecycle stages.

If a model is shared, deployed, audited, or embedded in a pipeline, it should come from the registry. Raw run IDs are too volatile to serve as a stable contract.

The registry exists to turn experimentation into something consumable.

Next step

To see these concepts in action, follow the full tutorial:

Model Registry End-to-End Demo

It walks through dataset curation, training runs, automated promotion, registry version creation, and inference from stored artifacts. The example is intentionally simple so the workflow can be adapted to real projects.